- ERC Tax Return Amendment Rules Change - March 25, 2025

- Safe Financial Instruments Guide - December 4, 2024

- New Overtime Rule Increases the Salary Exemption Thresholds - November 19, 2024

Do you have a Question?

Ask below. One of our Investors or Advisors will Answer!

In this post, we explain how many businesses are valued based on a measurement known as EBITDA or Adjusted EBITDA.

Valuing a business starts by understanding:

- How the EBITDA Measurement is Used to Value a Business

- The Importance of the EBITDA Multiple

- How to Calculate EBITDA (free tool) and

- The Valid Adjustments to Compute Adjusted EBITDA

One of the many questions asked by business owners as they plan for the sale of their business is related to the Adjusted EBITDA definition. Its computation is important to business owners because it’s a vital part of a multi-step process used in the valuation of a privately held company.

Adjusted EBITDA is used by Business Brokers in the valuation and sale of smaller businesses often referred to as ‘Main Street Businesses’. Likewise, the concept is used by Merger & Acquisition Intermediaries or Investment Bankers when representing businesses for sale in the lower middle and middle market.

Before we define Adjusted or Normalized EBITDA, understanding what this measurement means in the context of business valuation is a worthy exercise.

How to Value a Company

Main Street and Middle Market Business Valuations use a variety of measurements to determine an approximate fair market value of a business. Neither the valuation methodologies nor their underlying measurements are carved into stone. Instead, each industry or type of business tends to use a variety of valuation techniques to suit its own needs.

For example, a professional services business like an Information Technology (IT) company, is valued typically on a multiple of 1 to 1.5 applied to (or multiplied by) its annual gross revenue. Alternatively, businesses in other industries may rely more heavily on the Adjusted EBITDA measurement to determine business value.

Generally speaking, the greater the business’s gross revenue, the more likely its business valuation will be derived in part by the Adjusted EBITDA measurement.

EBITDA Multiple

As mentioned above, a ‘multiple’ is applied to a given measurement such as annual gross revenue or Adjusted EBITDA to determine the business value.

The product of this multiplication is one component in the business valuation. Additional adjustments may be made for assets and liabilities associated with the business operation or entity.

The EBITDA multiple also varies widely from industry-to-industry and even from year-to-year. When M&A activities increase, the EBITDA multiples used in business valuations tend to rise. When business acquisitions are less attractive in the private markets, the EBITDA multiples tend to drop.

While much debate exists over which business valuation methodology and measurement should be used, suffice it to say understanding the ‘Adjusted EBITDA’ concept is a worthy exercise for the entrepreneur. It’s useful because this measurement tells a business buyer how much cash a business produces on an annual basis. And such a measurement becomes more important to both the seller and the buyer as the business grows its annual revenues.

Before we explore Adjusted EBITDA’s definition, let’s define EBITDA and show you how to calculate it.

EBITDA Calculation

EBITDA is an acronym for Earnings Before Interest, Taxes, Depreciation and Amortization.

Most business owners don’t focus on this measurement of cash flow from operations until it’s time to understand it in terms of business valuation. And often that doesn’t happen until the business owner begins his exit planning or selling process.

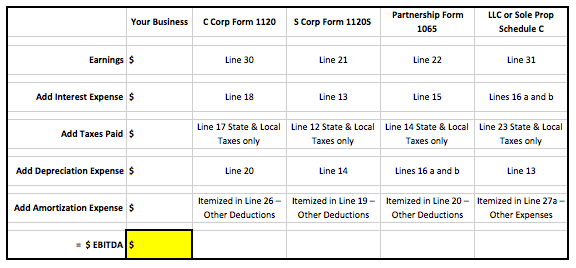

Here’s a simple formula to calculate EBITDA from the figures found on your 2017 business federal income tax returns:

Adjusted EBITDA Definition and Calculation

The EBITDA measurement of cash flow from operations often only tells the owner or buyer of a business part of the story.

In most private businesses, certain forms of income and expenses are not standard. Instead, it is safe to say anomalies related to certain income and/or expenses may exist.

Accordingly, to get a true picture of the business’s cash flow, an outside party will need to normalize EBITDA measurement. By normalizing EBITDA, a business buyer is better able to compare the cash flow from one business to another. In fact, another name used by M&A advisors for Adjusted EBITDA is ‘Normalized EBITDA’.

A few of the adjustments made to normalize EBITDA may include:

Adjustments which will Increase EBITDA

• Excessive rent expense paid to a related party

• Excessive compensation and/or benefits paid to business owners, employees, relatives, etc.

• Excessive automobile expenses paid on behalf of business owners and/or employees

• Excessive travel and entertainment expenses paid on behalf of business owners and/or employees

• Charitable contributions

• Legal, Accounting and other professional fees not related to the ongoing operations of the business

• Excessive or lavish office related expenses

• Excessive bonuses paid to business owners and employees

• Bad Debts expense outside of the normal range

• Any expense considered discretionary and not customary to the industry by the business owner and/or management

• Any expense considered outside of the normal costs to operate a business such as a lawsuit settlement paid to another party

Adjustments which will Decrease EBITDA

• Excessive Management Fee Income from a related party or related business

• Excessive Rental Income outside of normal rental rates for the market

• One time windfalls such as a lawsuit settlement received

Once a business owner, his M&A and valuation advisors, as well as any potential buyers are able to reach agreement with regard to an Adjusted EBITDA figure, this key measurement is then used in the formula to determine the business value.

While this measurement is calculated on an annual basis, it’s not unusual for buyers to review the previous three years’ Adjusted EBITDA. By doing so, a buyer is able to assess the normalized cash flow trend and compare it to the gross revenue sales trend for the same three year period. If the two trends are consistent, it’s reasonable to assume additional sales growth in the future will result in an increase in cash flow. Of course this situation is desirable and exactly what a business owner should strive to achieve as he plans for a sale or business ownership transfer.

Exit Promise Members — Download your EBITDA Calculator!

Hi…If a company being sold has a 66 2/3% ownership in a related company, should the earnings from the related company be excluded when calculating EBITDA for the business valuation of the company being sold? thanks

Donyl:

It would make little sense to exclude the net income of a business that you are a majority stakeholder in. What if that child company was responsible for 99% of the parent company net income? Would you exclude it? Of course not!

So, regardless of the impact on the parent company financials, an asset of which you are the majority owner should definitely be included in the parent’s EBITDA calculation.

If you are selling ONLY select assets of the parent company and not the entity as a whole, then you could exclude an asset that is not part of the sale.

We are in discussion with a national strategic buyer. We started discussion before COVID hit and at that time we were literally half the size we have grown to now. If, at that time they offered a 5x multiplier for EBITDA (not at LOI point yet), and our EBITDA has gone from $350K to almost $750K is it unrealistic to ask for a higher multiplier of 6? We have a very strong EBITDA ratio (25%+), consistent growth expectations (lots already in the pipeline), located in a great and growing market, and our industry is very much in demand for consolidation and acquisition.

Hi Chris,

Congrats on your success. Very impressive!

The 5 times multiple is strong — even in the pre-covid era.

It may be possible for your multiple (for valuation and offer purposes) reaches 6 or even higher. It really depends on the type of buyer as you know. Strategics will pay more.

One thing to keep in mind though is if your revenue is in the $3M range ($750k/.25 EBITDA), typically the multiples don’t go very high. The more revenue a business has, the higher the multiples rise. It’s especially so when a business reaches $10M or beyond. Your business isn’t there yet.

One other big factor that affects multiples is whether your business has a customer concentration or not. If it does, the multiple will be lower.

Given you’re talking to a strategic buyer in the pre LOI stages, they may not (and should not) have access to your customer list yet. So their 5 times multiple may change if there is a customer concentration. Ditto if there is a supplier concentration that’s not tied up with a strong, written agreement.

Hope this helps Chris.

Happy to speak with you if you’d like. Here’s where you may schedule a call with me.

Good luck!